As a teenager in the early-’90s, splashing out on a second-hand copy of Car Ferries of the World ’88 by Yoshiho Ikeda and Taiki Takeda seemed like a pretty big investment. I’d found the book mentioned in the listings of an antiquarian book seller and, intrigued, sent off a cheque for, I seem to recall, ?20. Several days later the 186-page volume in both English and Japanese text arrived in the post.

The authors’ task had been to provide technical details, a photograph and perfunctory commentary on every car ferry on the planet with a gross tonnage in excess of 5,000grt as at December 1987. It’s fair to say that the book isn’t entirely comprehensive and a few ships were missed here and there; but as with many of these ferry time capsules it provides a remarkable portrait of a moment in time.

Flicking through my purchase I was drawn originally to the familiar British and European ships and, I have to confess, found the 20% of the book containing black and white images of the ferry fleets of the authors’ home country easy to skip over. The colour pictures on the covers, however, were something else. In particular I lingered over the three on the back cover – sandwiching a fine view of Travemunde was one of a clutch of Tirrenia vessels of varying vintage lying at Genoa and another of a busy Japanese port with a large terminal building fronting a row of car ferries of different operators, all berthed with their bow visors open. A four-symbol Japanese caption identified the port.

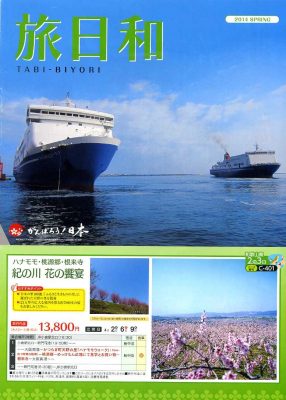

Twenty years later, I found myself on that very stretch of quayside, staring into the car deck of City Line’s Ferry Fukuoka 2 and struck by a tremendous sense of deja-vu. The port was, it turned out, Osaka’s Nanko ferry terminal and when I paid a visit there in 2012 to photograph the ships on their berths I was very quickly sure this was the same port I had admired all those years earlier. Later study of the original picture showed that, shoreside at least, remarkably little had changed – the Ferry Fukuoka 2 was berthed in the same place, at the very same ramp and in front of the same terminal building as the same company’s Ferry Hakozaki in the mid ’80s (the operator had yet to adopt the City Line name and were still known as Meimon Taiyo Ferry in those days). On the next berth I found the Orange 8, direct successor to the 1983-built New Orange seen on the same adjacent berth in the 1980s image and which operates between Osaka and Toyo.

Meimon Taiyo Ferry was the product of a 1980s merger between a pair of the ferry operators established in Japan’s 1970s ferry boom. Meimon Ferry and Taiyo Ferry both operated services across the Inland Sea but it is Meimon’s Osaka to Shin-Moji route, established in 1973, which has persisted in a market which is still fiercely competitive. Meimon’s first ship was lost in a collision with a tanker but the second, the Ferry Atsuta, would survive to become Minoan Line’ El Greco in 1979. Coincidentally Taiyo Ferry’s first ship would also end up with Minoan Lines – as their Daedalus.

The modern company operates two pairs of ships providing ‘early’ and ‘evening’ departures on its Shin-Moji route. The later departure is evidently the more prestigious, as successive generations of new ships are allocated to this with the elder vessels taking the earlier slots. The pattern of two pairs of vessels was established in the 1990s as the late ’80s sisters Ferry Kyoto and Ferry Fukuoka were paired with the Ferry Osaka and Ferry Kitakyushu (of 1992) before being replaced by the new Ferry Kyoto 2 and Ferry Fukuoka 2 in 2002. The first Ferry Fukuoka would, incidentally, end up with Stena’s brave but ill-fated South Korean venture, Stena Daea Line, as their New Blue Ocean.

The latest pair of newbuildings arrived in 2015 with the 1990s pair making way for a new Ferry Osaka 2 and Ferry Kitakyushu 2.

Two years after that eventful first visit to Nanko port, we were back again – and this time it was to board the Ferry Fukuoka 2 and sail on the company’s sole route between Osaka and Shin-Moji on the island of Kyushu. Presented below are some images from that crossing in May 2014.

As with so many Japanese ferries, the Ferry Fukuoka 2 and her sister were built just up the coast from Shin-Moji at the Shimonoseki yard of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries – which also produced P&O’s European Causeway, Ambassador and Highlander. The ships are very much overnight vessels with a restaurant the only real diversion other than the open-plan central square and the attractive upper arcarde. The idea of a ferry bar, so familiar to European travellers, is almost unknown in Japan and alcohol is available only from one of the vending machines on board.

Most passengers are on board to sleep, but few miss the highlight of the crossing, which is the passage beneath the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge, the longest suspension bridge in the world and a source of much wonderment and pride in Japan. This comes early in the crossing when travelling westbound, albeit usually after dark for the later departure, but most passengers seemed to stay up to watch it. The crossing also passes beneath the Seto-Ohashi Bridge and the Kurushima-Kaikyo Bridge although, despite approximate timings being provided by the on board guide, I doubt too many people were up to admire them.

The City Line vessels are genuine overnight ships with few general seating areas apart from the arcade, lobby and restaurant

To conclude, let’s go back to our port of departure and that 1980s view of Nanko ferryport. Whilst the port and terminal remain, sadly the ships seen in that picture have all long since left Japan. The New Orange was sold to China in 1999 after the arrival of the aforementioned Orange 8 and it’s not entirely clear whether she remains in service or not. The other three went to the Philippines, where the Ferry Hakozaki somehow survives, laid up as the St Joan of Arc. The Hamayu was less fortunate, burning out in dry dock in 2000 as the Superferry 3. The New Katsura was an earlier half-sister to the ship which became DANE Line’s Diagoras – she, however, ended up with Sulpico Lines as their Princess of the South. Spared one of that company’s regular calamities she managed to survive until being scrapped in 2014.